Hello world in assembly

I’ll use nasm as the assembler and ld as the linker ( more on this in time ). Code is for x86-64 Linux.

; comment

global _start ; start symbol, global needed by linked to know the first instruction

; ----------------------------------------- DATA ------------------------------------

section .data

msg: db "assembly", 10 ; 10 is code for newline, I cannot do "assembly\n" since this is not escaped so left i "assembly" + char with value 10

; ----------------------------------------- TEXT ------------------------------------

section .text ; the code section

_start:

mov rax, 1 ; 1 is syscall for write, put in rax

; this syscall is defined as ssize_t write(int fd, const void buf[.count], size_t count);

mov rdi, 1 ; arg1, 1 is stdout

mov rsi, msg ; arg2, address of "msg" as I defined above, I can add labels to addresses and assembler figures it out

mov rdx, 9 ; arg3, read 9 bytes starting at "msg"

syscall ; do the syscall with the current state of registers

mov rax, 60 ; exit syscall

mov rdi, 0 ; arg1, exit code 0

syscallTo run this,

nasm -f elf64 hello.asm -o hello.o # assemble to object file

ld hello.o # link to create executable

./a.out # run the executableglobal _start define a symbol with name _start visible globally. The linker NEEDS this to populate the address at which the program starts executing. This is placed in the ELF headers as

Entry point address: 0x401000

The placement of global _start doesn’t matter, I could’ve placed it anywhere in the file but as long as it’s there.

some_name: ... tags the address of the next instruction with some_name which I can use to refer to this instruction later. Note that the start of program is tagged with _start.

In the .data section I define read-only data, in this case a string. db means define byte and defines a sequence of bytes. The string is not null-terminated and does not need to be since I’m using the write syscall which takes a length as an argument instead of relying on a null-terminator.

The .text section contains the actual code. mov is simply move this into that register.

Why rax and 1? Where is this from?

This is how syscalls actually work in Linux. Link to actual source code which defines entry point for these syscalls in assembly is here

Note this section,

Registers on entry:

rax system call number

rcx return address

r11 saved rflags (note: r11 is callee-clobbered register in C ABI)

rdi arg0

rsi arg1

rdx arg2

r10 arg3 (needs to be moved to rcx to conform to C ABI)

r8 arg4

r9 arg5

(note: r12-r15, rbp, rbx are callee-preserved in C ABI)

How to figure out the syscall number? They are also defined in the kernel source code in syscall_64.tbl. Though an easier way to get these is through the header file /usr/include/asm/unistd_64.h which defines these as macros. cat /usr/include/asm/unistd_64.h

Now in order to get the documentation for the syscall, refer man 2 write ( 2 is the section for system calls in the manual pages ). From there you get the signature ssize_t write(int fd, const void buf[.count], size_t count).

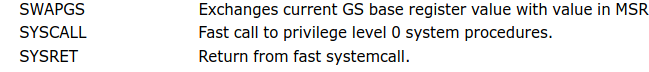

Note how the registers in which the args are placed match the expected registers in the kernel source code. syscall is then the actual instruction ( just like mov ) that performs the system call. This is a modern version of the int 0x80 system interrupt that was used in older versions of Linux ( and is still part of a lot of literature ).

This is screenshot from Intel’s manual at the time of writing this.

Assembler, Linker and can we do lower?

Writing assembly still feels like writing code, and I still need to compile to object file and link, which feels very much like any other language.

Firstly to answer: Can we go lower? Remember that it is still the kernel that executes the code, so I need to write in a format that it understands, aka, ELF.

Now, I can very well write the exact instruction as bytes, for example, instead of mov rax, 1, I could instead write the corresponding byte sequence but that is artifical complexity.

On a broad level, assembler generates the object files, it converts the assembly code into machine code for the CPU and puts stuff in sections. It also processes a single file so for cases where exectuable needs to use multiple files, the linker merges the inidivual object files into one, and hence assebler also adds stuff to relocation section for the linker.

To summarize, it processes a single file and convert the different sections into machine code.

Linker, puts the sections together into a memory layout that the kernel can understand ( basically shuffling around section, merging sections from different object files, resolving symbols ). This is what completes the executable file.

Why could it not be one step? Well you could always “treat” as one, wrapping the two steps into one and it would be no better. This is also how things traditionally evolved.

The object file

Looking at the disassembly using objdump -d a.out gives us the following:

hello.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .data:

0000000000000000 <msg>:

0: 61 (bad)

1: 73 73 jae 76 <msg+0x76>

3: 65 6d gs insl (%dx),%es:(%rdi)

5: 62 .byte 0x62

6: 6c insb (%dx),%es:(%rdi)

7: 79 0a jns 13 <msg+0x13>

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <_start>:

0: b8 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%eax

5: bf 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%edi

a: 48 be 00 00 00 00 00 movabs $0x0,%rsi

11: 00 00 00

14: ba 09 00 00 00 mov $0x9,%edx

19: 0f 05 syscall

1b: b8 3c 00 00 00 mov $0x3c,%eax

20: bf 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%edi

25: 0f 05 syscall

Note that the _start symbol is left ( also shows up in nm hello.o ) and this is what the linker uses to know what is the first instruction to execute.

mov $0x1,%eax instruction starts at 0 and takes up 5 bytes.

Just a little bit of x86_64 instruction encoding

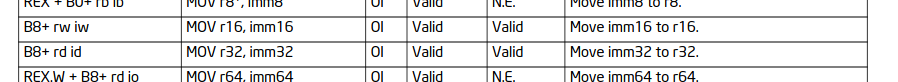

so as to make sense of some of the disasembly above. Why b8? On page 1255 of the intel manual linked earlier, we see this.

So b8 is basicaly mov immediate to eax ( this is a gross oversimplifification ). rax specified in code is a 64-bit register. So then why is the data after b8 only 4 bytes, and why is the register changed to eax?

These are optimisations done by nasm, since data is known at compile time ( since it’s immediate ) and it’s ⇐ 4 bytes, it’s encoded as a move operation to eax instead ( note for rax op code would be 48 b8 ).

It also shortens the data to be then just 4 bytes long.

So are there two accumulator registers on a 64-bit CPU? No, what this instruction does is move the immediate value to the lower 32 bits of rax ( eax is just an instruction construct, it’s the same register ) and do a zero-extend of the upper 32 bits so the value is same had it treated it as a 64-bit value. This is faster because your instruction is only 5 bytes long instead of 10 bytes needed for 64 bit move ( 2 bytes for opcode and 8 for immediate valuem, not all opcodes are 1 byte ). The zero-extend operation is very optimised and takes no cpu cycles.

For example,

mov rax, 8364700003 ; value larger than 4 bytes

get disassembled to

0000000000000000 <_start>:

0: 48 b8 63 31 93 f2 01 movabs $0x1f2933163,%rax

7: 00 00 00

which is 10 bytes.

After b8, value is stored as 01 00 00 00, shouldn’t it be 1?

This is because of the endianness of the architecture and x86-64 is little-endian, so the least significant byte is stored first. Note that it’s bits not bytes. Hence it’s 01 over something else.

What about the .data section?

What is the gibberish there?

Since I’ve done a -D, objdump tried to decode text as instructions but the result is not valid. If I do objdump -s to read it as text, I get,

hello.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Contents of section .data:

0000 61737365 6d626c79 0a assembly.

Contents of section .text:

0000 b8010000 00bf0100 000048be 00000000 ..........H.....

0010 00000000 ba090000 000f05b8 3c000000 ............<...

0020 bf000000 000f05 .......

which checks out. The last ’.’ is the newline character which not being in ascii range, is printed as as dot by objdump.

readelf -a gives me the stat of .data as 200

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .data PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000200

0000000000000009 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 4

Now reading this in hexdump -C ( -C else it interprets it as 16 bit and little endian so flips of characters like 6173 becomes 7361 ),

00000200 61 73 73 65 6d 62 6c 79 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |assembly........|

Why is this not reversed per little endian? The difference is that the string is a sequence of bytes not a multi-byte sequence, the endian-ness only affects multi-byte sequences but since a character itself is a single byte, it’s not reversed.

If I define some_number: dd 0x1 in the data section, it is stored reversed as 01 00 00 00 which is reversed per little-endian.

Note that the size of data secton is now 13 bytes ( 4 added for the dd aka double word aka 32 bit value ). How is one symbol distinguished from another if there’s no marker of sorts and the space is as much as the data itself? This is where the other sections comes in.

The other sections

List of all sections per readelf -a,

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .data PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000200

0000000000000009 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 4

[ 2] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000210

0000000000000027 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 16

[ 3] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000240

0000000000000032 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[ 4] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 00000280

0000000000000090 0000000000000018 5 5 8

[ 5] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000310

0000000000000016 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[ 6] .rela.text RELA 0000000000000000 00000330

0000000000000018 0000000000000018 4 2 8

0th is the null section. The ELF standard mandates that the first entry in the section header table must be a NULL entry with type SHT_NULL and all fields zeroed out. This is basically used a marker for undefined behavior and default value. If some section does not exist, you can refer to this entry. I’m not a 100% sure why this could not have been done better.

.shstrtab (section header string table ) is just the list of all sections and null terminated. So from readelf -x .shstrtab we get,

Hex dump of section '.shstrtab':

0x00000000 002e6461 7461002e 74657874 002e7368 ..data..text..sh

0x00000010 73747274 6162002e 73796d74 6162002e strtab..symtab..

0x00000020 73747274 6162002e 72656c61 2e746578 strtab..rela.tex

0x00000030 7400

Note that start is just a null character (0x00) for the null section.

.symtab is the symbol table ( this object file one contains no dynamic symbols ) and are defined as per the ELF64_Sym struct.

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 6 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS hello.asm

2: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1 .data

3: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 2 .text

4: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 1 msg

5: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT 2 _start

strtab is the similar to .shstrtab except for symbols shown above. readelf -x .strtab gives,

Hex dump of section '.strtab':

0x00000000 0068656c 6c6f2e61 736d006d 7367005f .hello.asm.msg._

0x00000010 73746172 7400 start.

Note that if you do the hexdump of the symbol table, you don’t see the strings, as they store offsets in the string table. This also explains the need of a null terminated string, else for the same space you would need to store end or length. Also explains the existense of the .shstrtab section since the section header table ( which is not a separate section ) refers to this.

.rela.text is the relocation table for the .text section. This is where the linker comes in.

.rela and linker

Disassebling the object file,

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <_start>:

0: b8 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%eax

5: bf 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%edi

a: 48 be 00 00 00 00 00 movabs $0x0,%rsi

11: 00 00 00

14: ba 09 00 00 00 mov $0x9,%edx

19: 0f 05 syscall

1b: b8 3c 00 00 00 mov $0x3c,%eax

20: bf 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%edi

25: 0f 05 syscall

Note assembly starting from a, there’s a mov but the immediate data is all 0. What I wrote was mov rsi, msg and msg is the address of the string in the .data section but since assembler just individual sections, it leaves this linking to be done by the linker ( I think I heard in some talk that on higher levels of optimizations it can also just fill in the address ). I’ve often heard of this filling in being referred to as “fix-up”.

But in the final executable after linking, this is converted to

40100a: 48 be 00 20 40 00 00 movabs $0x402000,%rsi

401011: 00 00 00

Also, this is what the relocation table looks like from readelf -r hello.o ( I assumbe this is stored in binary per some other ELF struct so no point in viewing that ),

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x330 contains 1 entry:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

00000000000c 000200000001 R_X86_64_64 0000000000000000 .data + 0

Note that this is relocation table for the .text so offsets are relative to start of .text

This reads as, at text offset 0x0c ( this is right after the mov ), Info is 64bit read as ( upper 32 bit = 2 = symbol table entry index, lower 32 bit = type of relocation ), Type is R_X86_64_64 which means 64-bit absolute relocation ( what this exacly does I’m not sure, I need to make sense of the values filled in by linker someday ). Addend is the offset from the symbol. This checks out from the symbol name being .data and addend 0 which is where the msg symbol is though I’m not sure why it did not refer to the msg symbol directly. Probably nasm uses a section relative address for relocation generation.

Index 2 in symbol table,

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 6 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS hello.asm

2: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1 .data

3: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 2 .text

4: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 1 msg

5: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT 2 _start